Over the last 10-15 years, we have found fundamental puzzles with the potential to significant change our understanding of each of the three major stages of galaxy evolution:

- Assembly of the ingredients that will eventually turn into a galaxy

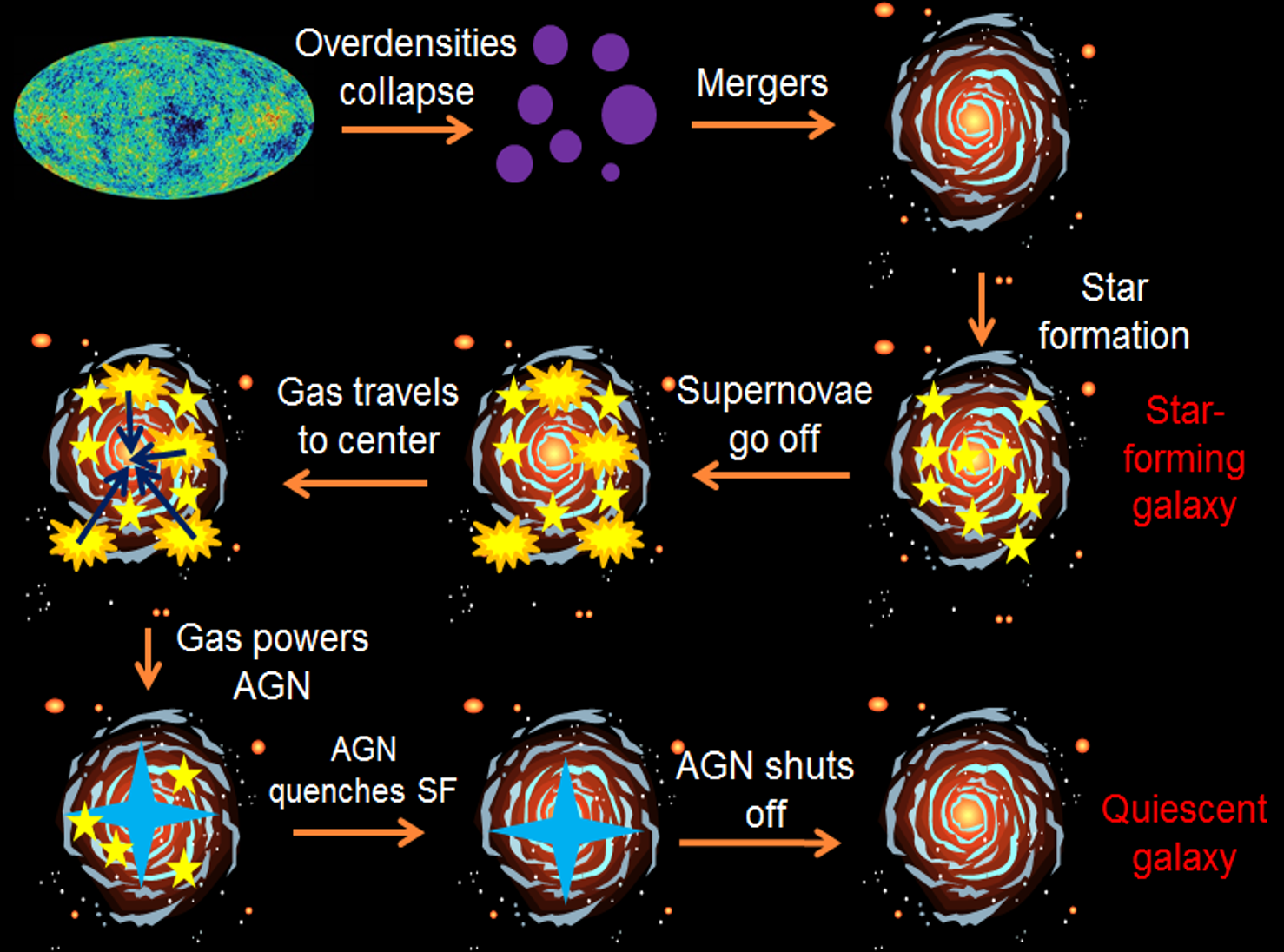

- Production of stars, a central supermassive black hole, and recognizable structure

- Galaxy “death”, or quiescence, with all of these growth processes stopping.

Observations of the brightest galaxies in the early Universe appear to reveal galaxies so massive that under standard cosmology, their ingredients would not even have had time to assemble, let alone also form a galaxy. If these masses are correct, an explanation might suggest the introduction of new high-energy physics in order to allow more rapid assembly.

Observations of both star-forming galaxies and rapidly-growing supermassive black holes find a surprising similarity and even synchronization to their growth. Even though galaxies live in a wide variety of environments, have different shapes, sizes, histories, and colors, they all appear to grow their stars and supermassive black holes in similar ways. Further, even though galaxies of the same mass are predicted to have assembled at different times, their later evolution is synchronized, even across the entire observable Universe.

Finally, observations continue to uncover “dead” galaxies at earlier and earlier times, with massive quiescent galaxies now having been found less than 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang. It is unclear why these galaxies not only evolve so quickly, but also remain quiescent even when their environments continue to provide fresh material which could be made into new stars.

How can we solve these puzzles?

The next decade is set to see the launch of two major new space missions, the James Webb Space Telescope, the most expensive basic research faculty ever constructed, and the Euclid, the largest astronomical collaboration in history. These will be paired with cutting-edge ground-based telescopes including the Atacama Large Millimeter Array and the https://www.eso.org/public/teles-instr/elt/ to allow first glimpses of the transition between the initial assembly and subsequenct evolution of galaxies, a period called Cosmic Dawn. I am a member of the Cosmic Dawn Center, a Danish National Research Foundation Center of Excellence focused on making full use of these new telescopes to answer these questions in the coming decade.

Prior to upcoming launches, my goal is to make full use of existing telescopes. I am the PI of BUFFALO, a large Hubble Space Telescope program which takes advantage of gravitational lensing from massive galaxy clusters to magnify distant galaxies which would otherwies be too faint for Hubble to observe. I am also a member of the SPLASH and COSMOS teams, which have produced a 2 square degree, multi-wavelength dataset responsible for many of the discoveries mentioned above, and the upcoming Cosmic Dawn Survey. At the same time, I develop theoretical models in an attempt to solve these puzzles, which can be tested by JWST and Euclid.

Key Recent Papers

- Steinhardt et al. 2020, “Thermal Regulation and the Star-forming Main Sequence”

- Steinhardt, Yurk, & Capak 2017, “Reconciling mass functions with the star-forming main sequence via mergers”

- Steinhardt et al. 2016, “The Impossibly Early Galaxy Problem”

- Steinhardt & Speagle 2014, “A Uniform History for Galaxy Evolution”

- Speagle, Steinhardt, Capak, & Silverman 2014, “A Highly Consistent Framework for the Evolution of the Star-Forming “Main Sequence” from z ~ 0-6”